Sapuan: Benguet’s Rare Indigenous Treasure

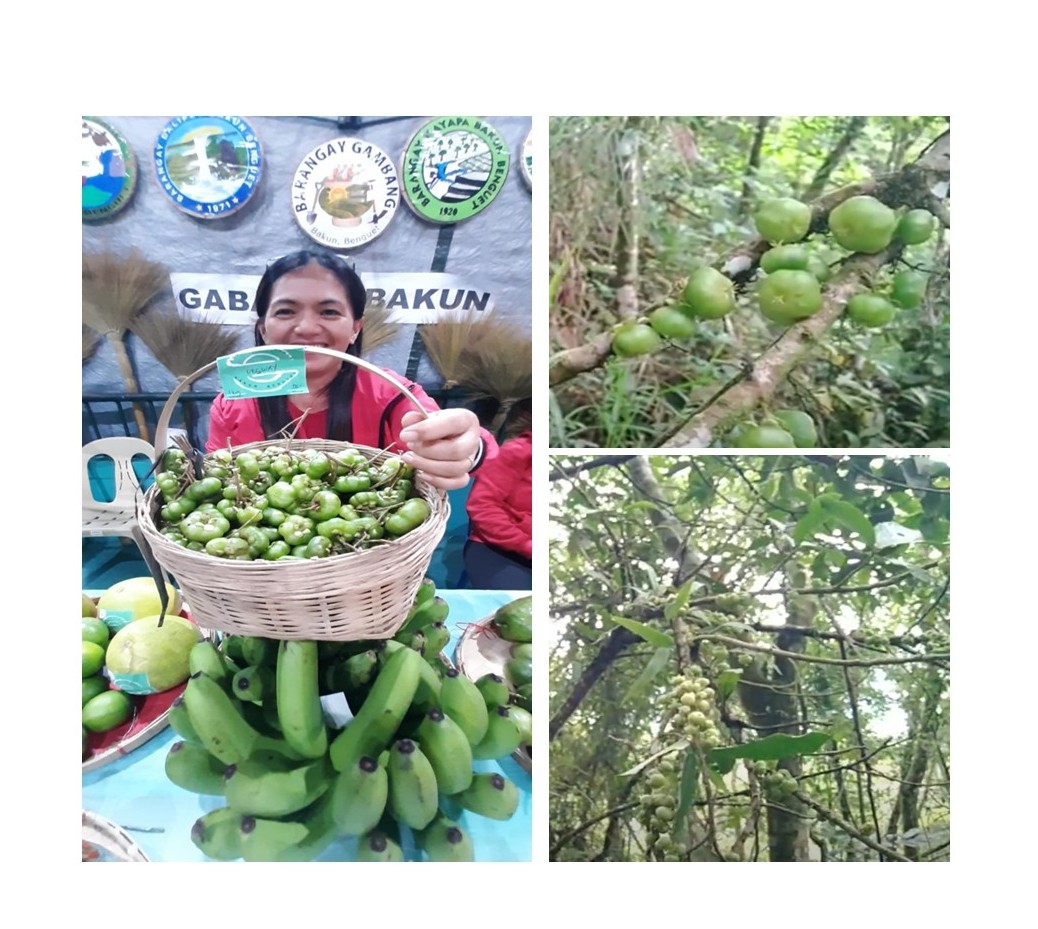

In Photo: FRUIT OF ABUNDANCE. Degway (Sapuan), a cherished indigenous fruit from Bakun, is showcased at the five-day Benguet MSME Trade Fair, held at the Provincial Capitol covered court, July 21–25, 2025. (Photo by Merriam del Rosario)

BAGUIO CITY — High in the misty mountains of Benguet, where pine trees sway in the cold breeze and the soil clings to roots for dear life, grows a fruit many have forgotten. Small, green, scalloped like a tiny pumpkin, it once hung heavy on the branches of trees that dotted villages and forest edges. In Ibaloi, it is called Sapuan. In Kankanaey, it is known as Degway.

For children who grew up in Benguet’s old mountain communities, the fruit was once a treasured snack. Picked fresh from a tree, dipped in salt, or thrown into a simmering pot of sinigang, it filled stomachs and strengthened bodies. “We are used to eating this fruit during our childhood years as a source of Vitamin C, but it seems isolated now,” recalls Tublay Municipal Agriculturist Jeff Dulay Sotero, who remembers Sapuan as a faithful guardian of children’s health.

Sapuan trees are modest in size, reaching no more than six meters, yet they are generous beyond measure. Each year, starting in June, their branches grow heavy with fruits that last for months. They thrive in the cool embrace of mountainsides and shaded areas, offering not just food but life to the ecosystem. The trees hold the soil, shelter birds and insects, absorb carbon from the air, and remind those who know them that abundance is not measured in gold, but in the quiet generosity of the land.

But like many indigenous treasures, Sapuan is slipping away. Retired agriculturist Felicitas Ticbaen remembers when the fruit was still plentiful in Tawang during the 1970s. Today, the once-familiar trees are nearly gone, cleared for houses or lost to forest fires. A few remain scattered in the barangays of La Trinidad — Talinguroy, Wangal, Beckel, Shilan, and Ambiong — as well as in the towns of Tublay, Bakun, Sablan, and Kibungan, where the fruits appear occasionally at trade fairs like shy reminders of what the land used to give.

Researchers at Benguet State University have shown that Sapuan is more than a childhood memory. Beyond being eaten raw, it can be processed into candies, jams, even decoctions, with branches that can serve as firewood. And yet, despite its gifts, it has been largely neglected — unstudied, unpropagated, nearly forgotten.

To Sotero and Ticbaen, Sapuan is not just a fruit. It is a story of survival and abundance waiting to be retold. It is a symbol of what the land can give if only people listen, remember, and care. They hope for more research, more community knowledge, and more government and NGO support to protect and propagate Sapuan before it disappears completely.

Imagine a Benguet where children once again run to the trees for Sapuan, their laughter echoing in the cool air, their health strengthened by the same fruit their grandparents once held in their hands. Imagine the pride of farmers cultivating Sapuan as an indigenous crop, its sour-sweet taste gracing kitchens once again, its name etched not only in memory but in the future of food security and cultural heritage.

Sapuan is more than a rare fruit. It is a reminder — that abundance grows quietly in the mountains, waiting to be cherished, nurtured, and shared.